THE EXPERIENCE OF TIME IN VISUAL IMAGES

As a topic, how we experience time in visual images might be an art history essay or a small book. But my aim here is modest. I am ignoring time as a theme in works of art. Videos are beyond the scope of this short article. I am interested in understanding why time, which seems to be an intrinsic element in a photograph or a painting, is perceived differently in the two disciplines.

Images in photography and painting could be placed on an imaginary spectrum, which ranges from a particular moment - a millisecond of time - to an expanded moment, which may stretch toward eternity. At one end of the spectrum are images so precisely rooted in the moment that they almost stop time. At the other end of the spectrum are images which seem nearly timeless. Let’s consider a couple examples of images at the extreme ends of the spectrum.

When I look at an icon, I experience an otherworldly timelessness. Iconography is incredibly time-intensive. Painting an icon with multiple layers of pure, hand-prepared pigments, and gilding it with 24-carat gold, require many exacting hours of labor. Iconographers use a symbolic language of color and form to represent Christ, the mother of Jesus (Theotokos), or the saints - all of whom have transcended time. Minimal shadows are cast from an inner light, but not from the sun of this world. Strong lines define the image, further emphasizing its existence in another dimension. The priest's consecration of the image, and the veneration of the faithful seal the image’s timelessness. With the passage of centuries, the paint will certainly fade and crumble, but for the faithful, the image exists in eternity.

Virgin and Child (with permission of the iconographer)

On the opposite end of my imaginary spectrum are photographic images. One of the strengths of photography is the ability of the camera to capture a precise moment in time. You’re probably familiar with photographs showing a lightbulb at the moment of impact by a pellet. It's unforgettable because our brain doesn't freeze the instant of impact for us.

Shattered Lightbulb ( Public domain, Huffington Post)

The shattered lightbulb is an extreme example. It may not qualify as “art”, but photography is celebrated for capturing the defining moments of our lives - as in French street-photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson's "decisive moment". Sometimes painters and sculptors share an interest with photography in capturing that defining moment. This shared interest seems to be the subject of Cartier-Bresson's famous photograph of sculptor, Alberto Giacometti.

Giacometti -photograph by Henri Cartier-Bressan (public domain)

On our imaginary spectrum, a photograph that captures the stop-action in a basketball game would be placed closer to the photo of the shattered light bulb than would a photograph of a still life.

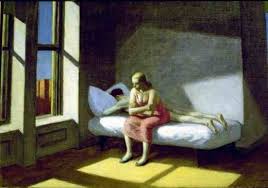

When compared to photography’s "Kodak moment" (a clever advertising phrase that once promoted Kodachrome film) paintings seem to have an expanded moment of time that is intrinsic to how we perceive the artwork. Consider two examples of expanded time in a painting. In some of Edward Hopper’s paintings, people in hotel rooms and restaurants look like they will not move for hours. Walls, windows, and shadows form broad, intersecting planes of stillness. Time stretches in these Hopper paintings. We know that drowned Ophelia, in John Everett Millais’ painting of a character in Hamlet, will never rise again. How we experience time in "Ophelia" is similar to the two Hopper paintings. The stillness of the figures is partly responsible for our perception of an expanded period of time, but what we know about painting may have a greater influence.

Hotel Room - Painting by Edward Hopper (public domain)

"Ophelia" - Painting by John Everett Malais (public domain)

Summer in the City - Painting by Edward Hopper (public domain)

If the paintings of Hopper and Millais were photographs instead of paintings, our sense of intrinsic time in the images would be different. I think the difference is based on our experiences in taking photographs and being photographed. Although photographs are not necessarily more “real” than paintings, our experiences with photography tell us that a photographic image (even one that is excessively photoshopped) captures an real instant in time. We know from experience that however long it takes the photographer to set up equipment and to wait patiently for the right moment, the camera can complete its work in the blink of an eye. When we view the resulting image, our experience with cameras shapes how we perceive time in the photograph.

When we look at paintings, our experience of time is not the same as with a photograph, as long as we see evidence of human touch. A Dutch painter of the 17th Century, Johannes Vermeer, may have used a camera obscura to make his paintings; however, his brushwork is evident when viewing the original oils. Knowing that the "Milkmaid" is painted by hand influences our perception of the moment of time depicted in the painting. "Milkmaid" looks photographic, but its intrinsic moment of time lingers longer.

The Milkmaid (c.1658) - Painting by Johannes Vermeer (public domain)

The importance of the human touch in our perception of time in an image is demonstrated by photorealistic paintings. Our experience of intrinsic time in photorealistic paintings is similar to a photograph because the artists are careful not to show any sign of human touch.

Photographs of some realistic paintings, intended for display online, are so reduced in size that the hand of the artist is less evident, and the missing element of human touch alters our perception of the image. Looking at reduced images of paintings which are more or less realistic is a far different experience than standing in front of the original paintings. (I encourage people interesting in owning a reproduction to order one closer to the original size so they experience the painting the way the artist experienced it.)

An art movement of the previous century altered our sense of time in a painting by combining separate moments of time into one image. Cubism, one of the painting revolutions of the twentieth century, provided us with painterly wrinkles in time, which are perhaps truer to our psychological experience of an object, but startling to see on canvas. Our knowledge and memory of a friend’s face, for example, is constructed in our mind’s eye from views at several angles over time. Cubist painters abandoned Renaissance perspective in favor of multiple perspectives. In the relatively flat, two-dimensional space of a cubist painting, our eyes take in almost at once several combined views of objects. We see from above, below and around. Multiple view points suggest movement in space, and that movement implies time.

Houses on the Hill - Painting by Pablo Picasso (public domain)

Cubist paintings altered our experience of time in an image, but they were still fixed in time. Another painting revolution of the previous century placed paintings nearly outside of time, similar to how we experience time in icons. The paintings of the famous abstract artists of the early 20th Century feel almost eternally present. Like the Byzantine iconographers of the Middle Ages, the paintings of the early abstract artists were concerned with the form and color of a spiritual dimension. Hilma af Klint, the earliest pioneer of abstraction, produced visionary paintings, which (for her) came from a metaphysical world where forms exist without beginning or end.

Svanen (Swan) - Painting by Hilma af Klint (public domain)

Hilma af Klint's marvelous paintings were intentionally otherworldly. In general, the closer a painting is to abstraction, the less bound in time it seems. For example, I’m fascinated by refraction of light in water. I’ve spent many hours on beaches staring at rocks under moving water, nearly hypnotized, trying to get a fix on the distorted patterns. Photography helps; nevertheless, the information in a photograph always requires many adjustments for a painting. I’ve taken multiple photographs of refracted rocks, and I’ve used a few of them to make paintings. My experience is that the closer the distorted images are to abstract patterns, the greater is the sense of expanded time in the painting, in spite of the fact that the image may show a moment of watery refraction.

Refraction - Painting by Nick Payne (copyright by Nick Payne)

The visibility of human touch in a painting tells us it took time. So does the knowledge that a painting is constructed over a longer period of time relative to most photographic images. Whatever the sources for a painting - reference photos, sketches, studio props, memory and imagination, or working en plein air - the creative process of painting is labor intensive. Anyone who has drawn something, even a doodle, understands that it takes time. When I look at a painting, I am aware that a painting is made by hand, and I am aware of the hours involved in constructing a painting. That awareness expands my sense of intrinsic time in the painting.

In contrast to painting, our photographic experiences tend to bind photographs to a moment in time. We point our cell phone cameras at a subject, press a button...and we can instantly share the resulting image over the Internet. Professional photographers take more time to process their photographs using computer software, such as Lightroom or Photoshop, but their results usually preserve a specific moment in time because our experience with photography tells us that a photographic image is time bound.

However, technological advances in computer software and printing enable some photographers - the digital artists - to create images that, more often than not, also expand the sense of intrinsic time. At the beginning of this article, I imagined a two-dimensional spectrum which ranged from a particular moment to an expanded moment. With digital art, the imaginary spectrum curves in space, like a strip of paper wrapped around a sphere. Digital art and painting meet at the extremes.

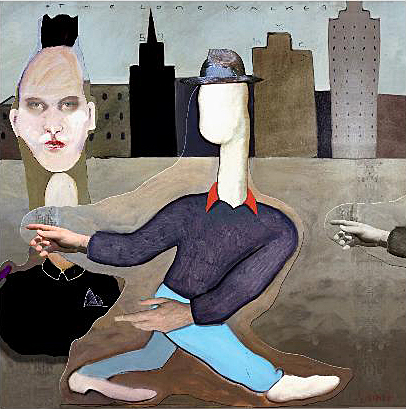

Some artists mingle photography and/or digital art with painting, creating an unusual, hybrid art. The relationships between the photographic elements and painted elements in the hybrid art play with how we experience photography - which feels more time specific and "real" - compared to how we experience painting - which is not as fixed in a specific moment and which feels less real. The tension between the photographic and painted elements in Charles Villiers' painting is unsettling, a mirror of contemporary, urban society.

The Lone Walker - Painting by Charles Churchill Villiers (with permission)

Intuitively, most of us are aware that our sense of time in a photograph compared to a painting is different. There is nothing profound in that observation. In thinking about it, I've concluded that our perception of intrinsic time in a photograph or a painting is mostly determined by what we know about the two disciplines. At the beginning of this article I wrote that my aim was modest. If your appreciation of photographs, paintings, and digital art has been slightly enriched by this article, I have achieved my aim.

2016 copyright by Nick Payne