Art washes away from the soul the dust of life. - Picasso

Since my teenage years I have been a fan of Pablo Picasso’s art. According to most art critics, Picasso was a genius of Twentieth Century art. Along with Georges Braque, he invented cubism, a revolutionary way of seeing. Picasso fully developed the concept of multiple perspectives. His artwork paved the way for non-representational art and collage. Artists who came after him explored and developed the use of the grid; rough, energized brushwork; strong color combinations; an emphasis on surface and shallow space; and the use of abstract notations. He did nearly everything in art, except go totally abstract.

Unlike some of his contemporaries who pushed their art to full abstraction, Picasso kept his work tied to subject matter. Picasso could have titled his abstract painting of 1948 “Composition with Line and Circle” and joined the abstract artists, but he connected the painting to his physical reality with the title, “The Kitchen”. Some viewers claim to see Spanish tiles, bird cages, plates, stove hotplates, and more in the painting.

“The Kitchen” by Pablo Picasso

Although many of Picasso's paintings and drawings appear nearly abstract, he resisted pure abstraction as a painter. “There is no abstract art,” he said. “One must always begin with something.” (Herschel Browning Chip. 1968, p. 270) Had Picasso spent time with the abstract paintings of Mark Rothko, he would have said they were about color. Rothko might have agreed. “There is no such thing as a good painting about nothing,” Rothko claimed.

“Orange and Tan” by Mark Rothko

I think Picasso rejected total abstraction for other reasons. He would have rejected abstract artwork which claimed to have a spiritual basis, such as the works of Hilma af Klint, Wassily Kandinsky, or Arthur Dove. While he thought that art had magic, he denied the existence of God. Sometimes, however, his statements contradicted his denial. He told Matisse that in times of trouble, it was good to have God on one’s side. And once, according to Olivier Picasso, he told Helene Parmelin, “If a painting is really good, it is because it has been touched by the hand of God.” Whatever his true beliefs about God, Picasso had no doubts about his own power to create.

I suspect Picasso rejected abstraction because it was outside the focus of his art. Pure abstraction had no purpose for him as a painter because abstraction would eliminate the subject of his art, which was mostly about himself and his mental and emotional responses to his circumstances. He had a grand sense of his importance. Picasso told one of his mistresses, "When I was a child my mother said to me, 'If you are a soldier, you will become a general. If you are a monk, you will become the Pope.' Instead, I was a painter, and became Picasso." ("Life with Picasso", by François Gilot. 1964, p. 60)

For Picasso, abstract art is mere decoration when it is unmoored from subject matter. In his words, “I have a horror of so-called abstract painting.…When one sticks colors next to each other and traces lines in space that don’t correspond to anything, the result is decoration.” Unlike Picasso, I admire the abstract paintings of many artists; however, I agree with Picasso that in the hands of lesser artists, abstract art can seem lifeless.

In my early years I had several art teachers. I couldn't study in the Louvre Museum like the renown painters of France, but I poured over reproductions in books and frequented the galleries and museums of Seattle. Picasso was one of my favorites. I carefully studied his work and read biographies. Through the years as I learned more about his life, I had to separate my admiration for his art from my dismay at his cruel treatment of friends, and especially the women in his life.

When Francoise Gilot first met Picasso, he was sixty-two and she was twenty-one. She gave birth to two of his children, Claude and Paloma. After ten years she left him, the only one of his many mistresses to do so. Her book "Life with Picasso" appears to be an honest account of life with a brilliant artist and sometimes an abusive, self-absorbed man. Picasso unsuccessfully tried to suppress its publication. I recommend her book. (Sorry, Pablo.)

Sometimes Picasso failed to be his best with others. Most people have failed a family member, a spouse, or a friend at some point, and depending on who is telling the story people who are generally good can be made to appear very bad. Picasso’s grandson, Olivier Widmaier Picasso, in his book, “Picasso: An Intimate Portrait” offers a sympathetic viewpoint of his famous grandfather. I enjoyed the book and recommend it as a counterbalance to more severe critics of Picasso’s character.

Also in Picasso’s favor, it could be said that in his formative years Picasso and his circle of friends and fellow artists were rebelling against prevailing standards in art and against the values of their parents and the prevailing social expectations. They partied all night and slept in late. They talked political anarchy, used opium, swapped partners, and produced experimental music, poetry, plays and paintings. I can overlook some of the youthful excesses of Picasso’s early years in Paris, which were similar to the Hippie excesses in the late 60s; however, Picasso’s intentionally cruel humiliation of his friends and lovers cannot be excused.

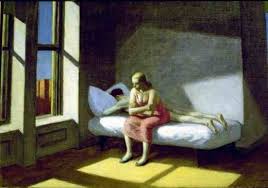

Nevertheless, every serious artist since Picasso eventually must come to terms with his art in some manner. I summed up what I learned from Picasso in two paintings of my twenties. (Needless to say, they are not the equal of a Picasso painting.) The two paintings are very different from the paintings I make today, but I've kept them because I'm sentimental about them.

My painting “Cavalier”, influenced by my interest in Picasso, attends to the formal elements of art, but it’s also a portrait. The figure and face is comprised of triangles and semicircles on a horizontal and vertical grid, but the aristocratic disdain of a cavalier is expressed in the painting, too. The largest triangle in the composition runs from its base at the bottom of the painting through the face, with the apex of the triangle between the eyes at the brow of the cavalier. The compositional device of the triangle is borrowed from Renaissance painters. Raphael typically used it to compose his timeless paintings of the Madonna and Child. In the “Cavalier” the Renaissance illusion of depth is absent. In keeping with the modernist canon, the “Cavalier” is flat and two-dimensional. The three-quarter view of the face combined with a profile is full-on Picasso.

“The Cavalier” by Nick Payne. Acrylic. 3 feet x 4 feet.

Picasso’s rearrangement of the face and body was initially shocking and disturbing, but psychologically it made sense. Our memory of people is a jumble of images from multiple viewpoints in various times and places. True enough, our memories of family, friends, and acquaintances don't look like Picasso paintings, but Picasso wasn’t replicating the jumble of images and multiple viewpoints as they exist in the mind. He artistically represented the multiple images of visual experience by synthesizing them into a single, flattened image. His use of color was somewhat dissonant like the revolutionary music he knew from designing sets for modern ballets. Space was usually shallow, or not represented in his paintings. To the three dimensions of height, width, and depth of a painting, it could be said that he added the dimension of time, which was implied in his multiple viewpoints.

“Portrait of a Woman” by Pablo Picasso

Picasso developed a new visual syntax; yet, no artist works outside of history. Picasso, like many artists of his time, was aware of the use of multiple perspectives in Cézanne’s paintings. For example, if you study the painting below you’ll notice tilted planes and subtle shifts in perspective, as if Cézanne changed position and viewpoints when painting.

“Still Life with Basket of Fruit” by Paul Cézanne

Notice the tilt toward the picture plane of some pots and the upward sweep of the floor. Trace with your eye the top of the table from left to right. The left side is closer. The right side is further away, as if the artist moved forward and backward and up and down while sketching and painting different sections. The large basket of fruit impossibly rests on the rear of the table.

“Cubist Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler” by Pablo Picasso

In this portrait of Picasso's art dealer, the hands and features of the face are visible, but most of the image is broken into multiple viewpoints and forms. Color is suppressed. As a portrait, the painting is almost unreadable.

Cubism developed the idea of multiple viewpoints to an extreme. Some cubist paintings are so abstract that we need the title to tell us the paintings represent real objects of our world. However, beyond the tenuous connection to real life objects, cubism is solidly rooted in form. (Form and color are the two building blocks used to construct a painting.) “Cubism is...an art dealing primarily with forms, and when a form is realized it is there to live its own life.” ("Picasso Speaks". The Arts, vol. 3.

Most painters have a consistent style. The co-inventor of cubism, Georges Braque, stayed with cubism throughout his career. Picasso, however, worked in many different styles in a variety of mediums. For him, each drawing or painting called forth its own approach and style, whether nearly abstract or classically realistic. In an interview published in 1923, Picasso said, "If the subjects I have wanted to express have suggested different ways of expression I have never hesitated to adopt them." (Cowling & Mundy 1990, p. 201)

Monsieur Picasso was one of my favorite art teachers because his art is so rich. The lessons about structure which I learned from his paintings are still with me, and my lifelong admiration for his artwork remains.

2017 Copyright Np